Total Therapy Blog

Cognitive Restructuring: The ABCD Approach to Negative Thinking

This article was written by our Clinical Counsellor, Kate Bilkevitch

I believe that the main purpose of counselling is to help you achieve empowerment to cope with various life situations, reduce emotional stress, and attain personal growth. I truly believe in the eclectic approach to counselling, which means that I draw upon multiple theoretical perspectives in my clinical work. My approach is always guided by your individual needs and concerns.

Cognitive Restructuring

Have you ever heard the term Cognitive Behavioural Therapy? Though fairly new in comparison to other psychotherapeutic approaches, this type of therapy has gained significant popularity over the last few decades. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT for short) is an evidence-based modality of psychological treatment, which has demonstrated excellent results in the treatment of various psychological issues including anxiety, depression, chronic pain and many others.

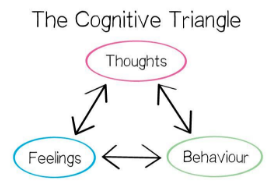

The CBT model was developed by several prominent psychologists including Aaron Beck and Albert Ellis. The idea behind the CBT approach is that our thoughts, feelings and behaviours are all interconnected. CBT proposes that our thoughts have a direct impact on our feelings and consequently on our behaviours. Moreover, our behaviours can then in turn affect our thoughts and feelings, creating certain cycles. You can think of this model as a triangle (see picture below).

For instance, imagine that you were in a rush and forgot to put enough money into the meter to pay for parking. Imagine returning to your vehicle an hour later only to find a ticket on your windshield. What might your thoughts and feelings be? Would you think negatively about yourself? Would you feel upset? How would it affect your behaviour?

The ABCD approach proposes that we can understand our thinking in the following way. An Activating Event (A) occurs. In the example above, the Activating Event is getting a ticket. The event activates a set of Beliefs (B). For instance, in our example you may think “I always forget such important things”, or “I can never get anything done right!” Consequences (C) of the activating event + belief is what you may feel. In the example above it could be the feeling of frustration, guilt or even feeling depressed. In the ABCD model D stands of Disputation – but we will get to this one a bit later.

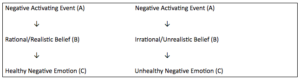

In the Event → Belief → Consequence model the belief can be either realistic or negative/unrealistic. Take a look at the diagram below.

Sometimes we would follow the sequence in the left column. With the parking example, you may find yourself thinking “Oh, I am pretty absent-minded today!” and you may feel a bit upset about getting a ticket. However, occasionally we will find ourselves following the sequence in the right column. Some end up gravitating to the negative set of beliefs (e.g. I always mess up, I can never get anything right, I am stupid etc). Thus, the goal of CBT therapy or CBT exercises would be to learn to 1) identify the negative beliefs and 2) substitute these negative/irrational beliefs with the realistic ones.

The second bit is what we refer to as Disputation. Disputation (D) is a way to change the sequence of events from the right column to the left column. D stands for “disputing” the negative thinking you discover in B, which in turn can affect how you feel in C. By substituting the negative beliefs with realistic/rational beliefs you will change the outcome of the situation, i.e. how you feel afterwards. Note that I purposefully avoid the term “positive beliefs”. Your goal is not to “sugarcoat” things, if you will. Rather, what you want to learn to do is to find a more realistic assessment of the situation. For example, if you forgot to pay for parking and the negative belief that arises out of it is “I’m stupid”, you do not want to simply state “I am not stupid, I am smart.” If you did that, how useful do you think it would be? Probably not that much. However, what if you disputed the negative belief with something like “I am not stupid, I have done plenty of smart things in my life. Perhaps I am more absentminded or forgetful because of the recent stress.” Or something along these lines.

Psychologists have grouped the various negative thoughts (cognitive distortions) into several styles of negative thinking. Below is a list of some common styles (that many of us use) as well as some possible ways to address these cognitive distortions.

- Catastrophizing – Sometimes we tend to imagine the most negative/worst possible outcomes. If you cannot reach a loved one on the phone you suddenly start thinking that something bad has happened to them. When you find yourself catastrophizing there are a couple of things you can do. First, you can ask yourself: what proof do I have that the worst will take/has taken place? Another good technique is to allow yourself to play out the worst-case scenario (loved one is not answering the phone because something bad happened to them), then go into the best possible, but likely unrealistic scenario (loved one won the lottery and wants to come home in person to break the news), and finally into the most realistic, middle ground (loved one’s phone is on mute, they are in a meeting, they lost their phone etc).

- Blaming – You may blame something or someone or, as often is the case, yourself for a given situation: “It’s completely my fault this happened!” To dispute such negative beliefs you can remind yourself that you made the best choice you could, given the circumstances: “I have made reasonable choices based on my understanding of the situation at the time.”

- Should/Must Statements – Shoulds and musts tend to be criticizing in nature as they imply that you were not smart or not strong enough (to act in an alternative way). Such statements can contribute to perfectionism. Essentially, when you use the should/must statements you put unreasonable demands on yourself and reprimand yourself for not being perfect all the time: “I should have thought of the consequence before I did something.” To dispute this you may remind yourself: “No one, including myself, need to be perfect all the time.”

- Polarized/Black and White Thinking – Things are only black or white, good or bad. There are no in-betweens and there is no gray area in the middle. It is important to learn to see shades of gray. If you performed poorly on a test, instead of thinking “I am stupid” you would reframe it to “I did not do well in this exam, but I have done well in other classes. Perhaps biology is not my strongest subject so I need to study more for it.”

- Emotional Reasoning – This style of thinking assumes that if you feel something is true then it must be true. That is, we mistakenly perceive our emotions as evidence for the truth. “I feel something bad will happen during this trip”. But just because you have this feeling, does not make it true. There likely is no concrete evidence that something bad will happen during your trip. To cope with this negative thinking style it is important to remind yourself that the only evidence you have is your feeling, and that it likely clouds your reasoning ability. Take some time to acknowledge your feelings and then set them aside and look for concrete evidence. Tell yourself that feelings do not always allow for an accurate assessment of the situation.

References:

- Beck Institute. https://www.beckinstitute.org/get-informed/what-is-cognitive-therapy/

- Pain Resource Centre. Cognitive Restructuring: Challenging Your Thinking. http://prc.canadianpaincoalition.ca/fr/cognitive_restructuring_challenging_your_thinking.html

- Clinical Depression. All or Nothing’, or ‘Black and White’ Thinking and Depression. http://www.clinical-depression.co.uk/dlp/understanding-depression/all-or-nothing-or-black-and-white-thinking-and-depression/

- Grohol, John M. 15 Common Cognitive Distortions. https://psychcentral.com/lib/15-common-cognitive-distortions/

- Micallef-Trigona, Beppe . The Origins of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. https://psychcentral.com/lib/the-origins-of-cognitive-behavioral-therapy/

Follow Us!

& Stay Up To Date

BLOG